By Susan Larson, The Times-Picayune

December 05, 2009, 5:00AM

On a sunny Sunday morning, a diverse gathering of 30-plus people meet for Mass at the small chapel Uptown at the corner of Henry Clay and Magazine streets.

Some light candles for special requests, others offer up concerns in their morning prayers. A baby cries, is taken outside in her mother’s arms, then returns, soothed. It is a ritual as old as time, this sound of murmuring human voices, sometimes lifted in prayer, sometimes in song.

All marvel at the nuns whose voices lead the service, particularly Sister Helen-Carroll Petty’s strong soprano. After greetings are exchanged, the members of the congregation drift off to their daily routines, but the nuns stay right where they are. This chapel, after all, is part of their home, the St. Clare Monastery.

When a Poor Clare takes her vows, she pledges chastity, poverty, obedience and enclosure. She enters a monastery to pray, to undertake a contemplative life. The monastery becomes home, house of worship, place of work and recreation, the setting for most of her life.

This monastery, built in 1912, is a lovely place to live — starting with its gorgeous chapel. Its extensive grounds fill a city block, part sanctuary (in every sense of the word), part park, part beloved Uptown landmark.

When a visitor arrives, seeking anything from spiritual counsel to Sister Mary Blosl’s famous pralines, she rings the doorbell for the monastery or its gift shop, and is greeted through a grate, also a signature feature of monasteries. At one time, the nuns kept their faces hidden. Nowadays, the cheerful countenance of whichever nun has door duty greets guests.

Behind the walls

Entering the main hall, the sparkling linoleum floors, wood paneling and stairways that bear the soft, glowing patina of age, and comfortable though not ostentatious furnishings catch the eye. The walls, in soft neutral tones, bear religious art or crucifixes.

The first floor holds a dining room, kitchen, office, break room, library and rooms for visiting retreatants, as well as the chapel and the gift shop, an important source of income for the sisters.

The space seems open and comfortable. "Everyone always says it seems like such a large building for eight women," Sister Mary said. "But sometimes it’s hard to find a spot to be alone."

The monastery may be a grand building, but the nuns' rooms are spare, containing only essentials. 'The point, after all, is to leave the world - all that stuff - behind,' says Sister Charlene Toups.

Since the work of the Poor Clares is prayer and contemplation, everything in the monastery is selected for that end. So its wide hallways are clean and gleaming, with light flowing in through the windows. Orderly, utilitarian, serene. When life is cleared of the non-essential, it seems, there is room for contemplation.

Sister Charlene Toups, recently elected to a three-year term as abbess, gives a tour, weaving history and philosophy and spiritual wisdom into a seamless and witty narrative.

A New Orleans native, she entered the order in 1966. "I like to say I dropped out of college and into the monastery," she said. "I was driven by a real sense that the need for prayer would never change."

"This is built on the same plan as medieval monasteries," she continued. "The nave is the public chapel. Behind a wall is the choir, where the nuns gather for daily prayers, morning, afternoon and night."

There, the pews face each other, for the call and response of readings. Off to the right of the nave is a nuns’ chapel, where the women would worship in the days before Vatican II, when they were not to be seen by the congregation and so worshipped behind a screen. Now, they gather there for reflection and sharing.

Their real jobs

The Clares take prayer requests from all over the city, the country and the world. One local football coach used to ask the sisters to pray for the safety of his team, and, of course, for their victory. On a recent Sunday morning, the congregation prays for Coach Sean Payton’s Saints, as well as their own. Still others ask for prayers for the sick, the faraway, the lonely.

Mass at the chapel is open to the public each day, at 8 a.m. on Sundays and at 7:30 other days. "There’s a difference between solitude and isolation," Sister Charlene said. "True solitude puts you more in touch. Part of the contemplative life is to be for goodness, in whatever form it takes. Every religion has a contemplative tradition — Islam, Sufism. If we ever meet on the contemplative level, if we can pray together, there’s a chance for peace."

Rather than being withdrawn from society, the Clares are traditionally an urban order, with monasteries in the midst of or on the edges of cities.

"We need to be there, we need to pray for the needs of the city," Sister Charlene said. "People often say, ‘Oh, it’s so noisy here, with the sounds of the trucks turning the corners.’ But those sounds of the city are God’s sounds, too. The city makes our life possible. … We are not a democracy, but we are communal."

The library, where the sisters read, research and write, holds books on every dimension of spirituality and religion.

Sister Rita Hickey, the author of a brief biography of St. Clare, used these books in preparing a recent article for Justice, Peace and Integrity of Creation, a commission conducted for the First Order of Franciscans. Her title was taken from the writings of St. Paul’s letter to the Ephesians: "We have not here a lasting city."

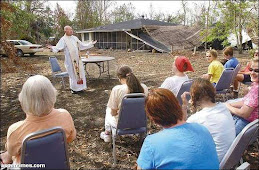

Her topic? The need for social justice, concern for the environment and fragility of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

The sturdy brick monastery withstood the storm, but the lack of power and medical services led the sisters to evacuate to a monastery in Brenham, Texas.

Photographer David Spielman cared for the building in their absence, and many of his photographs and experiences from that period appear in his book, "Katrinaville Chronicles," published by LSU Press in 2007.

Spielman has known the sisters for more than 30 years. "The minute I walk into that building, my blood pressure drops and a calm comes over me," he said. "If you walk through the building, you really sense their presence.

"It’s one of the most spectacular places I’ve ever had the privilege to live in. Some nuns are healers, some are educators, but the Poor Clares are all about praying, and you really feel that in the building. They’re a real treasure, the kind of people who make New Orleans so very special."

Communal lifestyle

In the airy, well-equipped kitchen, it is Sister Rita’s week to cook, and the daily menu is posted to allay diners’ curiosity. For this day’s lunch, Sister Rita is serving up red beans and rice (delicious!), greens, coleslaw and perfect golden cornbread, with fruit and leftover cheesecake for dessert.

The dining room is where the sisters relax, sharing their thoughts and their days.

After lunch, the sisters tidy up with speed of organization and custom. A visitor takes a turn drying the dishes; it’s obvious where things go. In the blink of an eye, order is restored and the kitchen and dining room are ready for the next meal.

The second floor holds bedrooms and offices and the "fun" library, which holds a collection of murder mysteries and New Orleans books.

Sister Olivia Wassmer welcomes a visitor into her second-floor studio. where she creates miniatures, paintings and Christmas ornaments — New Orleans landmarks in bright colors painted on balsa wood. Her sketches become stationery and bookmarks as well.

Mardi Gras beads adorn the entrance to her studio. "I caught those at the Thoth parade," she said, which is the sisters’ favorite. "You know, if you wear a veil, you get some really great stuff."

In addition to her work as an artisan, Sister Olivia is the monastery bursar and archivist, keeping its long history and studying the best ways to preserve it. She also plans the liturgy and plays the organ for services.

On the first Sunday in Advent, she celebrated her 57th anniversary as a Poor Clare. She came to New Orleans from a monastery in Evansville, Ind.

"Who wouldn’t want to come to New Orleans?" she asked. "And once you get here, you don’t want to leave."

What sorts of things does she pray for? Sister Olivia takes a deep breath.

"A sister called from Alexandria asking for prayers for a boy who’s 5 years old at Children’s Hospital. I put a poster on the bulletin board. And after prayers for the faithful, we talk about it at the table. But the individual I was praying for was that little boy. Every prayer request gets written in the book on the desk."

Like any artist’s studio, Sister Olivia’s is filled with the creative chaos of works in progress; she always introduces a new ornament the Saturday before Thanksgiving (this year’s is a replica of the Preservation Resource Center building), so this is a busy time of year for her.

She copies her original sketches onto balsa wood, paints in the colors, then applies five coats of varnish.

The greatest compliment she’s ever received, she said, is from a woman who evacuated with her complete set of ornaments.

Sister Rita, who came here in 1963, is taking a break from kitchen duty.

"Want to see where I work?" she asks, and heads down to her studio in the basement. A former civil rights worker, she too was drawn to a life of prayer. A Barack Obama poster hangs on the wall across from her worktable.

"I wanted to put it on my bedroom door," she said, "but some thought it wasn’t appropriate."

She does ceramics, and her trusty kiln Casimir is ready to be filled with a new batch. Like Sister Olivia’s space, hers is filled with works in progress, manger scenes and Christmas ornaments, renditions of her signature "Christmas critters" and angels.

She listens to the audiobook of Dennis Lehane’s bestseller, "Shutter Island," as she paints.

Sister Charlene makes candles at a nearby workstation, so even the spacious basement is a busy place. Her work originally began, as so many of the projects at the monastery do, "as total serendipity. Someone gave the monastery a quantity of wax."

She began experimenting with wax and beeswax, using leftover wax from chapel candles, and different perfumes and colors.

Around the grounds

The monastery grounds are extensive, including two live oaks named St. Anthony and St. Roch. There is a grotto, a grassy labyrinth and benches for contemplation. The backyard is entered from Magazine Street through an electric gate.

Sister Charlene Toups shows off the extensive grounds, which include a grotto, a grassy labyrinth, benches for contemplation and a vegetable garden."Best thing we ever did!" Sister Charlene said.

There is a vegetable garden, where the sisters grow lettuce, okra, green beans and squash, an herb garden ("the basil’s going to seed," Sister Charlene says), and a Meyer lemon tree loaded with fruit. Neighborhood children often refer to the area as "the secret garden," a tantalizing mystery behind that brick wall.

There is also a small brick building that is the monastery’s cemetery.

"We take you from cradle to grave," said Sister Charlene.

The small mausoleum is an island of peace, light streaming in through the partly open windows.

The sisters have Mass there in November, and it is easy to feel the pull of the sacred in this lovely gray space, with headstones marking those who have gone on. One grave is the resting place of Sister Marie Pius Patterson, the first African-American Poor Clare, who died in 1959.

Private locations

While a visitor may see sacred buildings, the nun also sees home. Bedrooms are simply furnished with a bed, desk, lamp and wardrobe. A pair of running shoes hang over a chair, prescription bottles are atop a dresser. Most rooms have crucifixes; some have family portraits.

Postulants who enter the monastery only bring what is necessary — their clothes, Sister Charlene says, and family pictures. "The point, after all, is to leave the world — all that stuff — behind."

There is a stubborn sweetness and strength about these women, so devoted to the welfare of others. Their lives are rigorous, fairly circumscribed by prayer, work, dining hours, contemplation and fellowship.

Yet they all have that mysterious twinkle, that sense of humor and mischief that makes them approachable, lovable. Their brown corduroy jumpers, T-shirts and denim skirts, seem the very apparel of grace.

They radiate love and goodness, a sincere concern for the world outside their gate. The eight of them — Sister Mary Blosl, Sister Eileen-Clare Duffy, Sister Fidelis Hart, Sister Rita Hickey, Sister Elizabeth Mortell, Sister Helen-Carroll Petty, Sister Charlene Toups and Sister Olivia Wassmer — are a family, and they do their best to make their visitors feel welcome in their home.

So what is the most difficult thing about living in a monastery?

Sister Charlene reflects for a moment. "Trying to stay focused," she said. "The world is so full of distractions. And of course you miss that edification of success. Community is always a challenge — but you learn to live and let live, give and receive, bear and forebear."

And of course, by their example of community, the Clares offer a model of how to live, if not exactly in the world, then beside it, wishing it well, offering up prayers for its welfare.

In this time of spiritual renewal, when the world seems so fractious and fragile, the sisters’ serenity is especially attractive.

"If we live the life God intended for us," Sister Charlene says confidently, "God will provide."

But will they be watching the upcoming Saints game? Sister Charlene says firmly, but with her trademark humor, "Some more religiously than others."

Photos by Kathy Anderson / The Times-Picayune

Source: The Times-Picayune

No comments:

Post a Comment